View in Public Interest Reports

This article, published in Public Interest Reports, a publication of the Federation of American Scientists, discusses the risk of nuclear war and different ideas for reducing the risks via policy work and other strategies.

The article begins as follows:

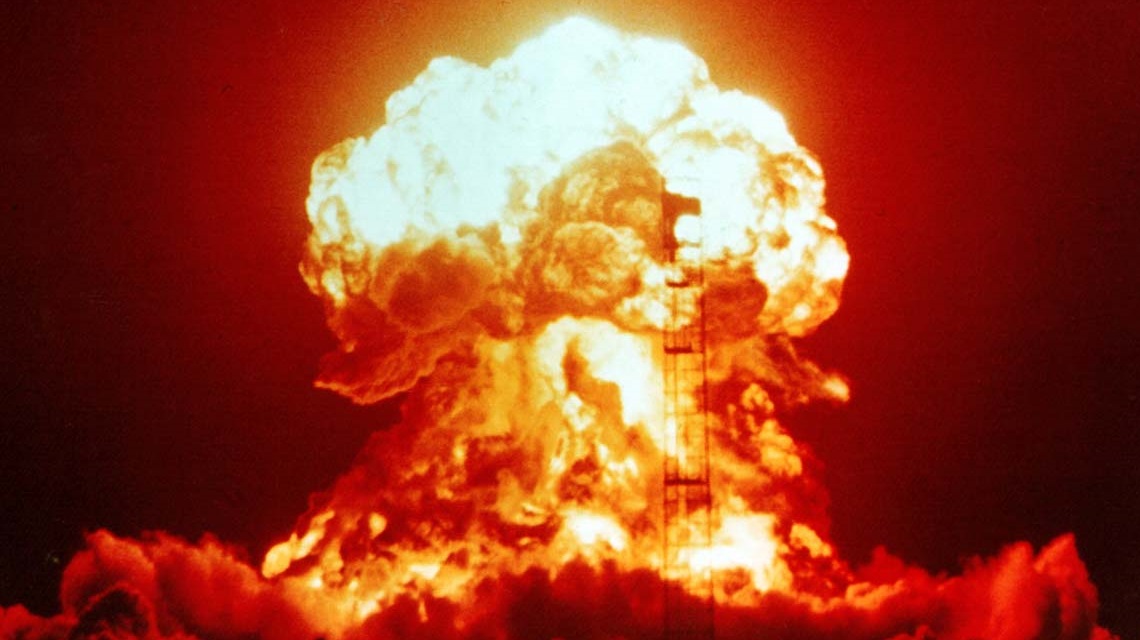

Since the early 1980s, the world has known that a large nuclear war could cause severe global environmental effects, including dramatic cooling of surface temperatures, declines in precipitation, and increased ultraviolet radiation. The term nuclear winter was coined specifically to refer to cooling that result in winter-like temperatures occurring year-round. Regardless of whether such temperatures are reached, there would be severe consequences for humanity. But how severe would those consequences be? And what should the world be doing about it?

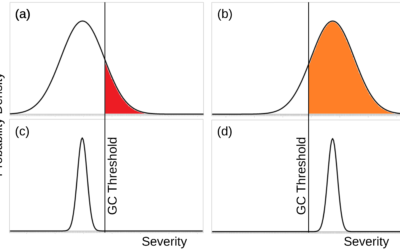

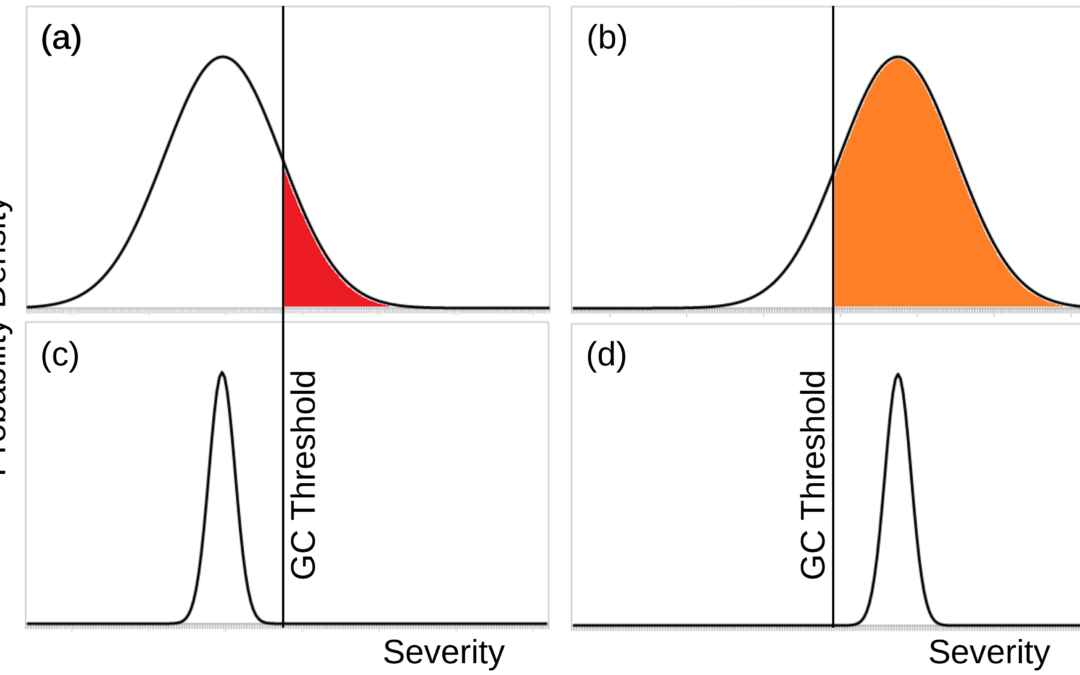

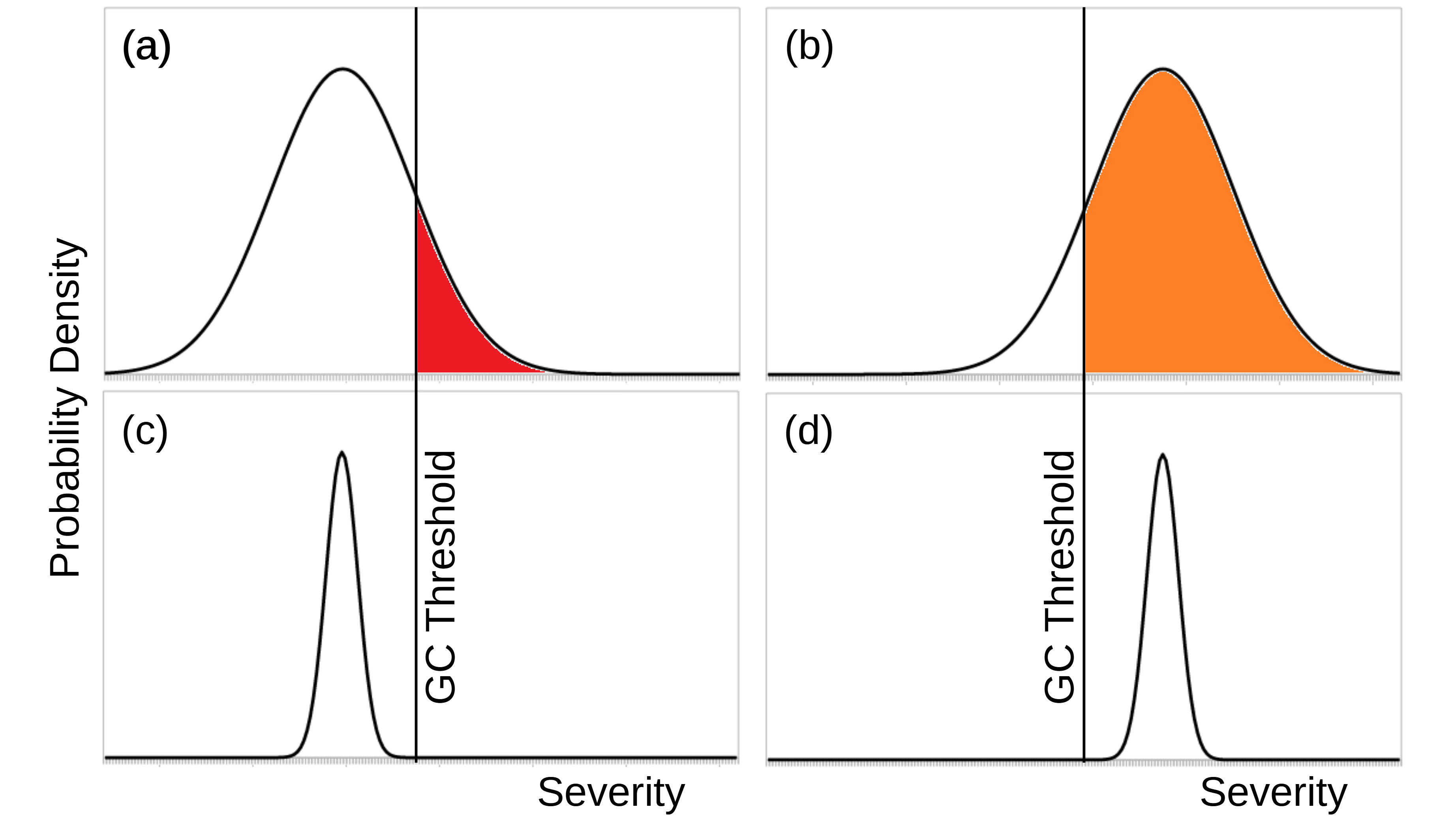

To the first question, the short answer is nobody knows. The total human impacts of nuclear winter are both uncertain and under-studied. In light of the uncertainty, a risk perspective is warranted that considers the breadth of possible impacts, weighted by their probability. More research on the impacts would be very helpful, but we can meanwhile make some general conclusions. That is enough to start answering the second question, what we should do. In regards to what we should do, nuclear winter has some interesting and important policy implications.

Today, nuclear winter is not a hot topic but this was not always the case: it was international headline news in the 1980s. There were conferences, Congressional hearings, voluminous scientific research, television specials, and more. The story is expertly captured by Lawrence Badash in his book A Nuclear Winter’s Tale.[ref]Lawrence Badash, A Nuclear Winter’s Tale: Science and Politics in the 1980s (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009).[/ref]Much of the 1980s attention to nuclear winter was driven by the enthusiastic efforts of Carl Sagan, then at the height of his popularity. But underlying it all was the fear of nuclear war, stoked by some of the tensest moments of the Cold War.

The remainder of the article is available in Public Interest Reports.

Image credit: US National Nuclear Security Administration

This blog post was published on 28 July 2020 as part of a website overhaul and backdated to reflect the time of the publication of the work referenced here.