This article, published by FutureChallenges, compares the challenges of recovering from local and global disasters. It argues that recovery from global disasters would be considerably more difficult because there would be no people from unaffected regions who can help the disaster region.

The article begins as follows:

Amid the dire tragedy of the 2010 Haiti earthquake, I was completely in awe of the world’s response. We seemed to be throwing every possible resource we could at saving lives and healing wounds. The logistics were challenging, as Haiti is an island country whose infrastructure was largely destroyed. And so I marveled at such technologies as the US Navy’s hospital ships. We have hospital ships? Fascinating.

A few years earlier, the disaster was on America’s coast. When Hurricane Katrina flooded New Orleans, many countries offered assistance to us. While we didn’t take much from other countries, much domestic assistance was deployed from around the United States.

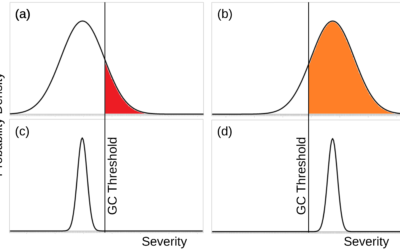

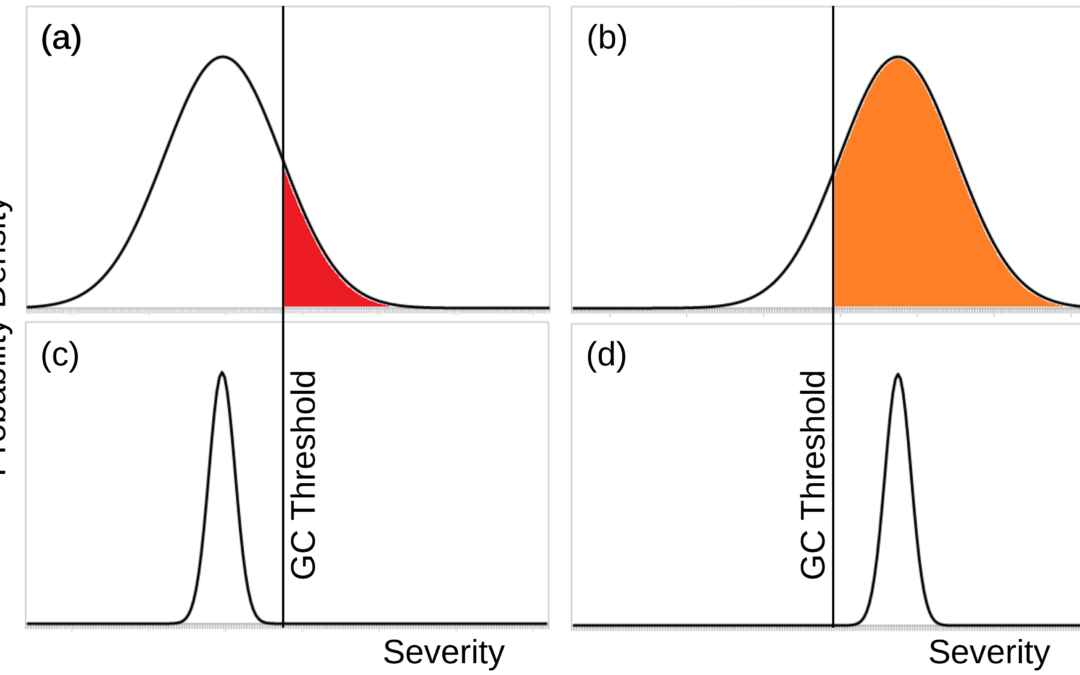

This geographically distributed approach is a hallmark of modern disaster response. In short, when conditions in one place become sufficiently severe, it is expected that people from other places step in to help, even if that means crossing international borders. We might think of this as a sort of insurance system, in which our inter-regional assistance prevents things in any one region from ever getting too bad. Here it is essential that governments have good relations with each other. Otherwise they may shun assistance, as happened after the 2008 Cyclone Nargis in Myanmar. In general, we can expect democracies to be much more likely to accept international assistance than totalitarian regimes, since distressed populations can be expected to want their leaders to accept help.

The remainder of the article is available in PDF archive.

Image credit: US Coast Guard

This blog post was published on 17 April 2024 as part of a website overhaul and backdated to reflect the time of the publication of the work referenced here.