A major challenge for work on global catastrophic risk and existential risk is that the risks are very difficult to quantify. Global catastrophes rarely occur, and the most severe ones have never happened before, so the risk cannot be quantified using past event data. An excellent recent article by Simon Beard, Thomas Rowe, and James Fox surveys ten methods used in prior research on quantifying the probability of existential catastrophe. My new paper expands on the Beard et al. study to further clarify the challenge of quantifying the probability. Note that all of the ideas here apply equally to quantifying the risks of global catastrophe and existential catastrophe.

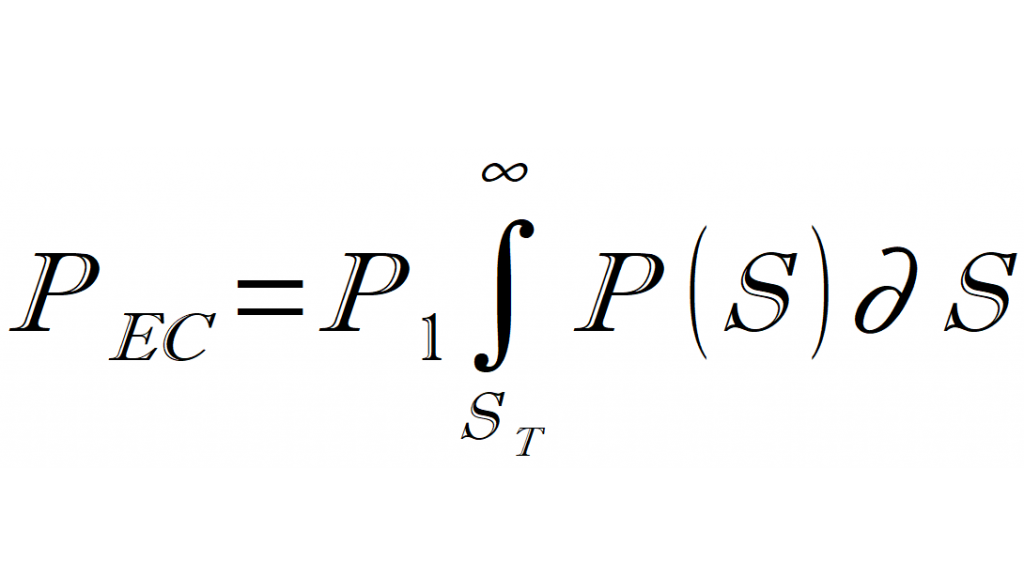

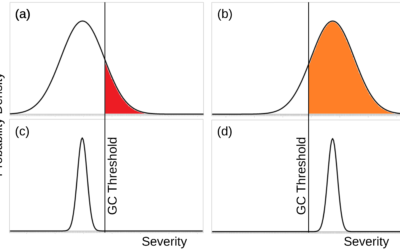

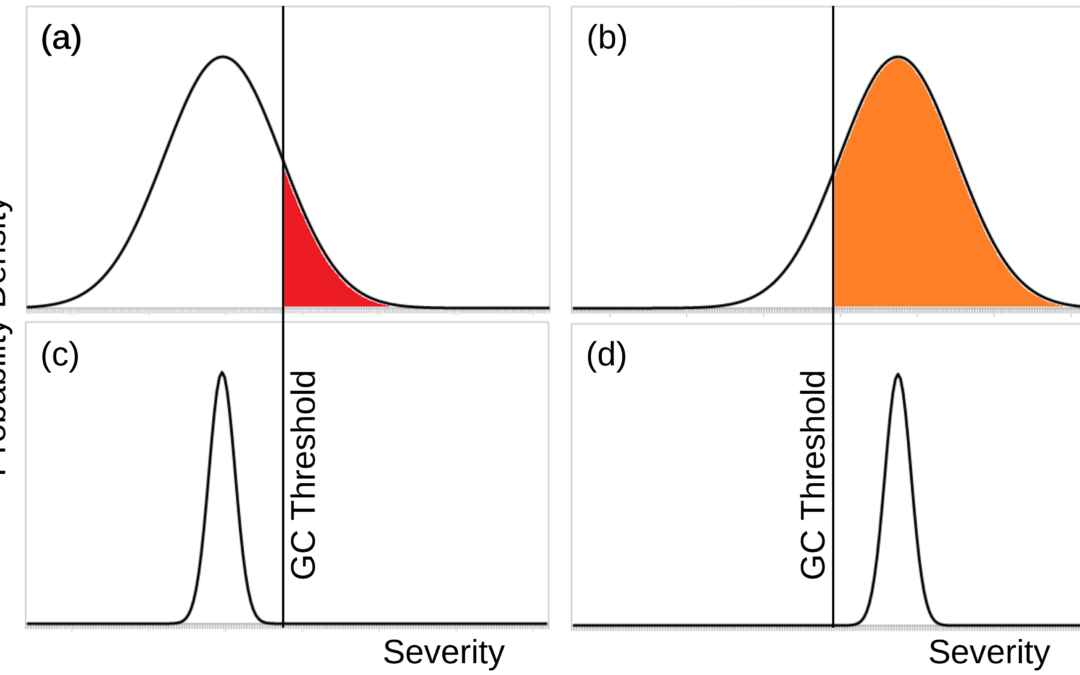

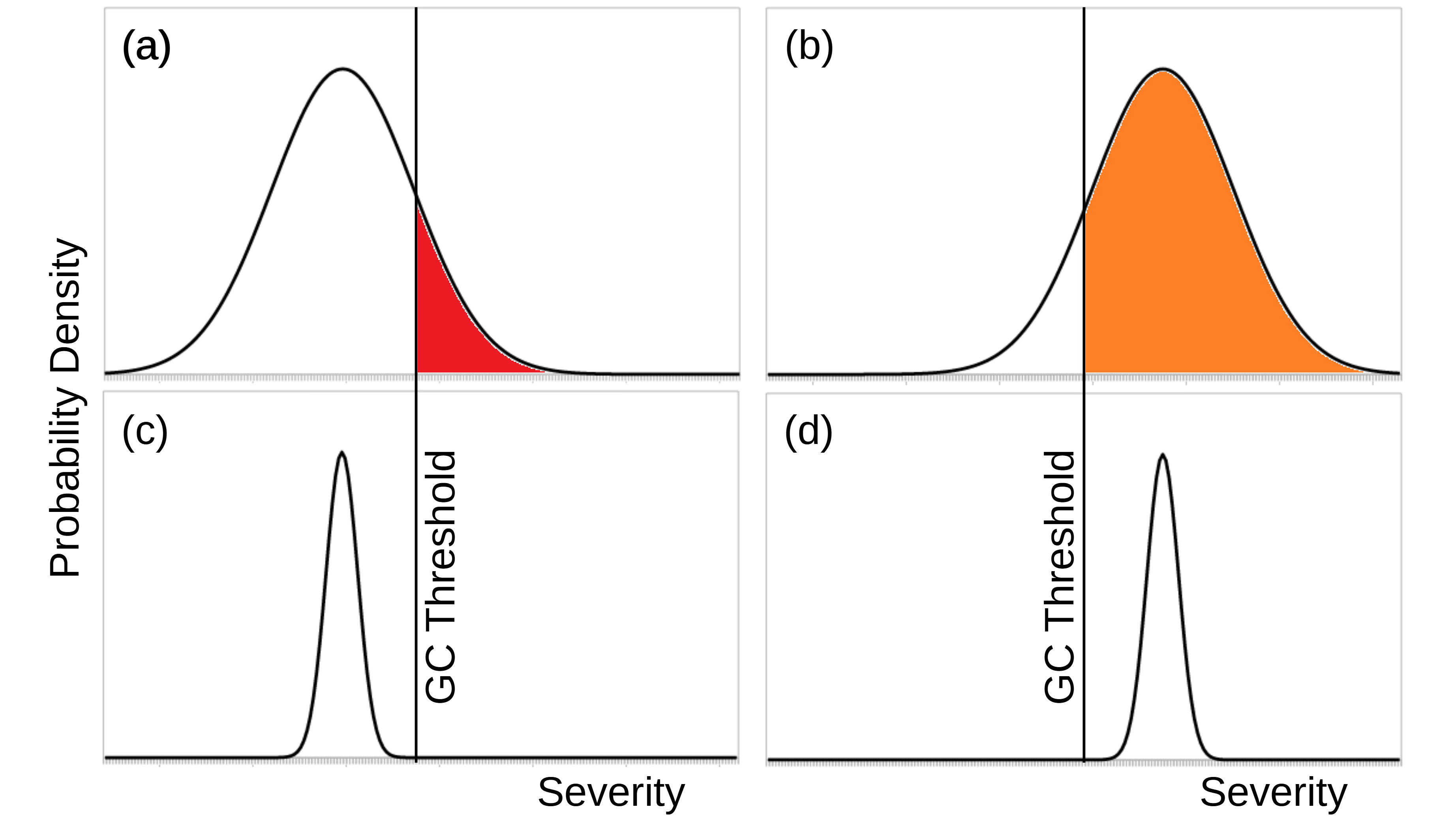

First, my paper relates the probability of existential catastrophe to its severity. Existential catastrophe is defined in terms of some minimum severity threshold. Beard et al. set the minimum severity of existential catastrophe at the collapse of human civilization. Other studies use other minimum severities, such as human extinction. However the minimum severity is defined, the probability of existential catastrophe is the probability that some event exceeds that minimum. This means that studying the probability of existential catastrophe requires considering both the probability of catastrophe events like nuclear war and supervolcano eruption and the potential severity of these events, in particular whether the severity would exceed the minimum threshold for an existential catastrophe. In other words, the probability cannot be studied separately from the severity. The equation pictured above captures this relationship. Therefore, quantifying the probability requires research on the aftermath of existential catastrophe. This is especially important for complex catastrophe scenarios in which multiple catastrophe events could combine to push the severity of the overall impact above the threshold. However, because most of the studies surveyed by Beard et al. do not quantify the probability of an event exceeding the severity of the collapse of human civilization, they do not actually quantify the probability of existential catastrophe as defined by Beard et al.

Second, my paper revisits the ten methods surveyed by Beard et al. Beard et al. evaluated the methods using four criteria. Three of them—rigor, uncertainty, and utility—capture aspects of the quality of the results produced by the methods. The fourth—accessibility—captures how difficult the method is to use. My paper shows a trend in the Beard et al. evaluations: methods that were good in terms of rigor, uncertainty, and utility were bad in accessibility and vice versa. This means that higher quality results are more difficult to obtain. They may be relatively easy to obtain for groups with experience with certain methods—for example, GCRI has experience with fault tree and event tree methods —but developing this experience can be difficult. Unfortunately, there are no shortcuts to good risk analysis.

Third, my paper discusses the role of quantifications of the probability and severity of existential catastrophe. Given the difficulty of producing quality quantifications, it should be understood that it’s not always necessary to do the quantifications in the first place. Arguably, quantifying the risk is important only when it affects actual decisions. If an action would reduce a risk without any downside, then it would be a good action to take regardless of the size of the risk. Also, the people who make important decisions about the risk often make them without using risk quantifications. Likewise, it’s important for risk analysts to be attentive to how the analysis could be used. Oftentimes, decision-makers are less interested in the numbers produced by a risk analysis than they are in the underlying analysis and what they can learn from it.

One overarching message of both my paper and the Beard et al. article is the importance of doing risk analysis well. It can be tempting to do quick, simple risk quantifications in order to complete an analysis, but it is easy to overlook the flaws in such work. Such flaws are avoided via quality analysis, but that is more difficult to do, and even then it may not be used in decision-making. Therefore, part of doing risk analysis well is knowing when quality analysis is worth the effort and when risk analysis is even needed in the first place. People working on global catastrophic risk have to understand these and other aspects of risk analysis methodology in order to make better decisions about what research to do and how it can be used to reduce the risk. For more information, please see GCRI’s work on risk and decision analysis.

Academic citation:

Baum, Seth D., 2020. Quantifying the probability of existential catastrophe: A reply to Beard et al. Futures, vol. 123 (October), article 102608, DOI 10.1016/j.futures.2020.102608.

Download Preprint PDF • View in Futures

Image credit: Seth Baum