The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is already the most severe global event in decades. It has killed more than 80,000 people and counting worldwide, left millions more out of work, and upended the lives of a large portion of the global population. We at GCRI are monitoring the situation closely and assessing opportunities to contribute to the outbreak response.

What follows are some initial thoughts on the pandemic. We expect to comment further as the situation unfolds.

What is GCRI’s primary message at this time?

We agree with the common message that it is important to slow the spread of the disease via social distancing, to increase the treatment capacity of hospitals, to test widely to track the progression of the outbreak, and, where possible, to trace the contacts of people with the disease to identify clusters of cases.

What is GCRI’s role in addressing the pandemic?

We are not experts on pandemics. Our own understanding of the COVID-19 pandemic draws heavily on the work of virologists, epidemiologists, medical professionals, and public health experts. We recommend following pandemic specialists to get accurate information about the pandemic. One good resource is National coronavirus response: A road map to reopening.

As the pandemic continues and the world adapts to this new situation, we expect GCRI to play a greater role in providing general perspective. Additionally, we expect to also contribute analysis of non-medical dimensions of the pandemic. For example: How should the world handle the possibility of a second catastrophe that occurs during the COVID-19 pandemic? This is the sort of question that benefits from GCRI’s expertise in cross-risk analysis.

There are at least two reasons for GCRI to get involved in the ongoing pandemic response. First, the COVID-19 pandemic is a global emergency. It arguably demands the attention and effort of everyone who is able to contribute to the response. Second, the pandemic provides us a rare opportunity to learn and prepare for future catastrophes, including more extreme global catastrophes. Thus, regardless of whether the pandemic technically qualifies as a global catastrophe (more on this below), it merits attention from groups like GCRI.

Is the COVID-19 pandemic a global catastrophe?

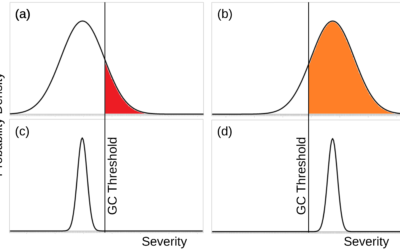

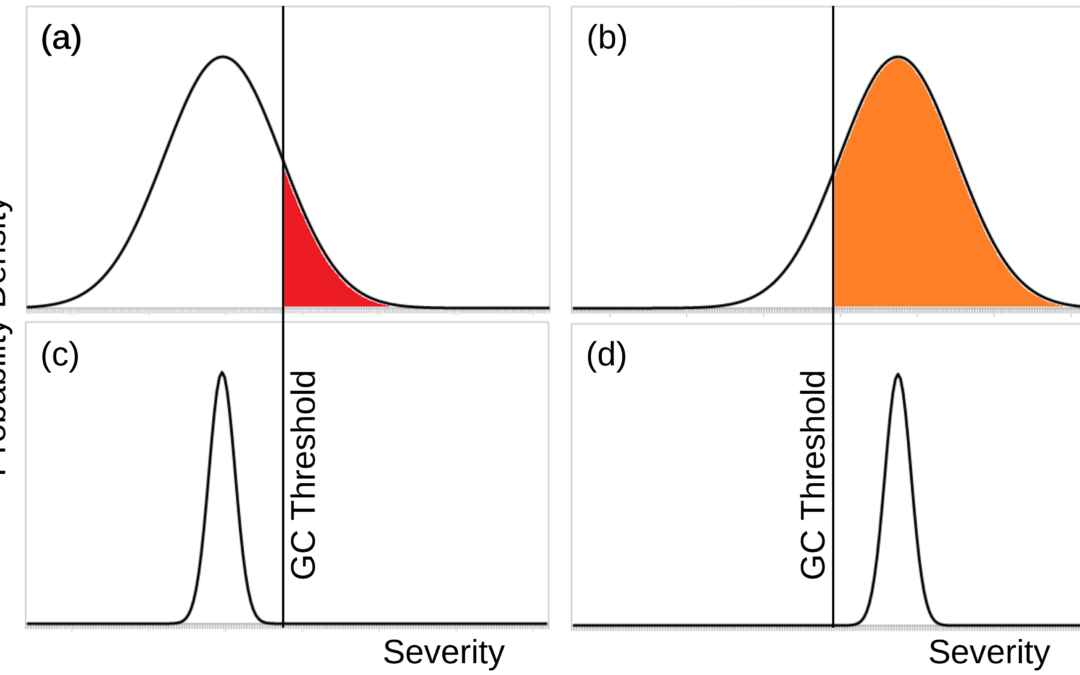

This question has an easy answer: it depends on the definition of “global catastrophe”.

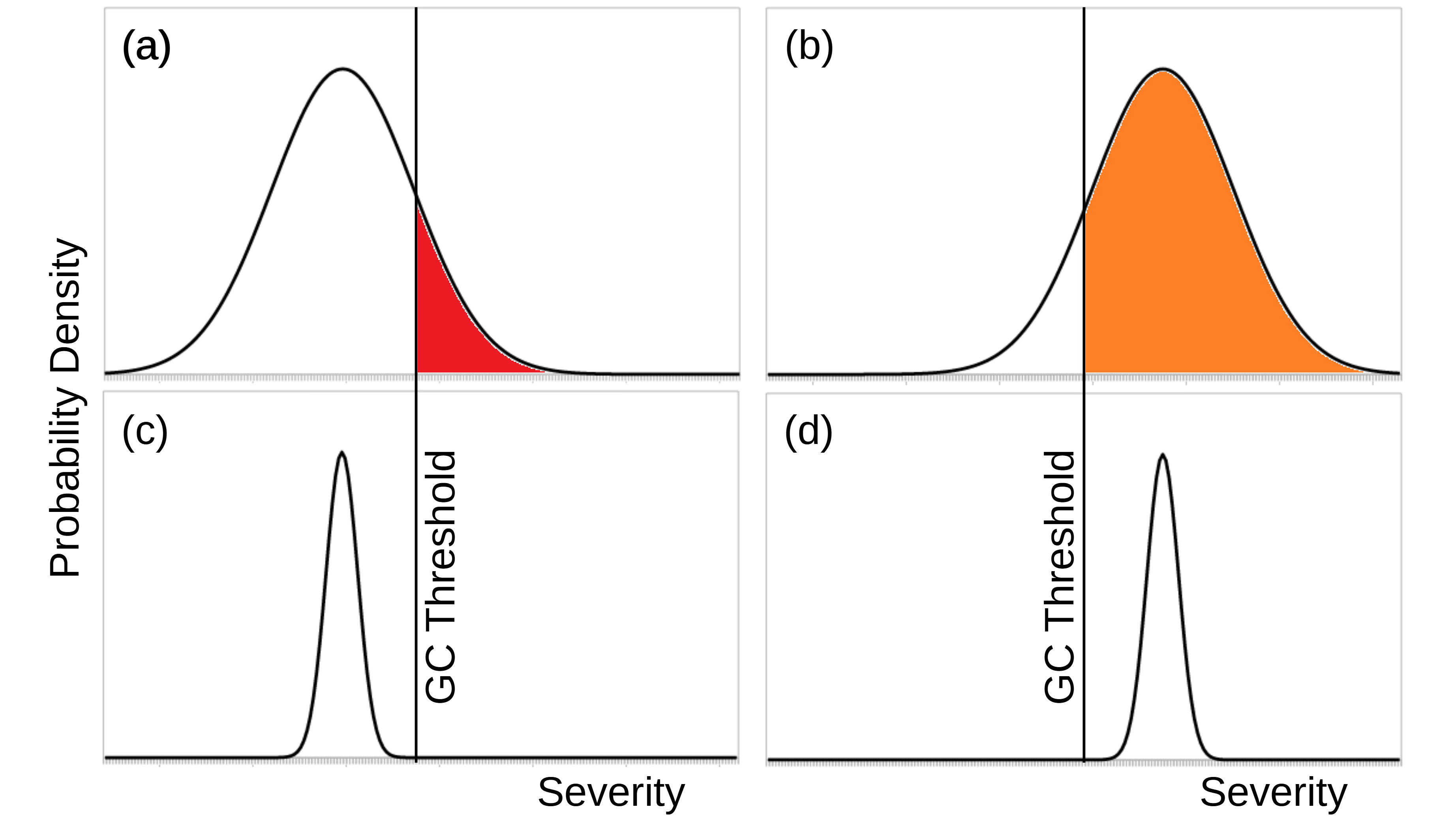

On one end of the spectrum, consider an event that resulted in the death of one person on each continent. This event would clearly be global, and it would be catastrophic for the affected parties. The COVID-19 pandemic is obviously a lot more severe than that, so in that sense it would qualify as a global catastrophe.

On the other end of the spectrum, an event would have to clear a much higher threshold to qualify as a catastrophe, like the death of 25% of the global human population or the collapse of global human civilization. These definitions are more common in the research literature on global catastrophic risk. By these definitions, the COVID-19 pandemic does not yet rate as a global catastrophe, and in our judgment is unlikely to ever rate as one.

One notable definition proposes that a global biological catastrophe occurs when a major biological event causes “sustained catastrophic damage to national governments, international relationships, economies, societal stability, or global security.” By this definition, both the 1918 influenza pandemic and the current COVID-19 pandemic could qualify as a global biological catastrophe.

What are some early lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic?

It is our view that right the primary focus should be on addressing the ongoing pandemic and not on reflecting on what we can learn from it. However, since deriving lessons from events is a GCRI specialty, we will provide some preliminary reflections here.

One lesson is that as bad as the current pandemic clearly is, future pandemics could be worse. For example, we could imagine a similar outbreak but with a higher fatality rate, especially among younger people. Worst-case pandemic scenarios generally involve a pathogen that spreads easily during an asymptomatic incubation period and then is highly lethal. COVID-19 spreads relatively easily, with reports of asymptomatic transmission. In addition, outbreaks of other novel coronaviruses such as SARS and MERS had substantially higher fatality rates than COVID-19. We should hope that the world never faces the outbreak of a disease that both spreads widely and kills at a high rate.

Another important lesson is to take seriously the warnings of catastrophic risk experts. The COVID-19 pandemic is broadly consistent with scenarios envisioned by pandemics experts, from its apparent zoonotic origin to its rapid global spread. In retrospect, the world would have been better off if it had heeded expert advice to improve surveillance of and rapid response to emerging infectious diseases. While there is no guarantee that any specific catastrophe scenario will occur, the ongoing pandemic demonstrates the value for preparing for the catastrophes that are reasonably likely.

A related lesson is that many people will not take experts seriously. Even today, some people, including some people in policy-making positions, still downplay the danger of COVID-19. In order to take constructive action on catastrophic risk, it is not enough for experts to identify what would in principle address the risks. It is also vital to account for the attitudes, preferences, and constraints of the people who need to take the actions. For more on this theme, please see GCRI’s work on solutions & strategy.

We at GCRI are optimistic the world will get through the COVID-19 pandemic. We sincerely hope that it will do so as safely as possible, and be able to avoid future catastrophes. We will do what we can to ensure that this happens.

Sincerely,

Seth Baum, Executive Director

Robert de Neufville, Director of Communications

Tony Barrett, Director of Research

Disinfection vehicles in Taipei image credit: Military News Agency