Aftermath of Global Catastrophe

Many global catastrophe scenarios do not result in immediate human extinction, instead leaving some survivors. This raises two questions: How well would the survivors fare? And what can we do now, before the catastrophe, to help them?

The aftermath of global catastrophe is a grim topic. It is about humans living in what could be overwhelmingly horrible conditions brought by a nuclear war, a severe pandemic, or some other extreme event. Civilization as we know it may no longer function: no more global economy, no more internet, no more electricity. In some scenarios, it even becomes difficult to grow plants for food. Survivors of the initial catastrophe must find ways to stay alive under these challenging conditions. They must also carry the burden of knowing that billions of their fellow human beings have died a tragic death. Discussions of nuclear war sometimes posit that “the survivors will envy the dead”. This may apply to all of the global catastrophe scenarios that leave some survivors.

Despite the dark nature of the topic, it is an important one to study and address. It is important for two types of decisions facing people in our current, pre-catastrophe world.

First, we face decisions about how to help the survivors of global catastrophe. There are many things we can do now to help them. We could design and manufacture technologies that would be of particular value post-catastrophe. We could stockpile food or develop new agricultural techniques to help survivors feed themselves. We could even build isolated refuges to help some people survive unusually extreme catastrophes. We could also work to increase the resilience of global civilization so that it doesn’t collapse if and when some extreme event occurs. These and other measures could substantially improve the fate of survivors. They could even be the difference between survivors rebuilding civilization (or preventing it from collapsing in the first place) and survivors dying out, ending in human extinction.

Second, we face decisions about which global catastrophe scenarios to prioritize. All else equal, it is better to prevent a catastrophe that would be more severe compared to a catastrophe that would be less severe. This follows from the basic idea of quantifying risk as probability times severity. How survivors would fare is a major factor in the severity. A catastrophe in which survivors die out is much more severe than a catastrophe in which survivors are able to prevent civilization from collapsing. Ideally, we would prevent both catastrophes, but given a hypothetical choice between the two, it would be better to prevent the more severe catastrophe. Actual choices that people face do often involve tradeoffs between different global catastrophic risks. In making these choices, it is important to account for how well survivors would fare.

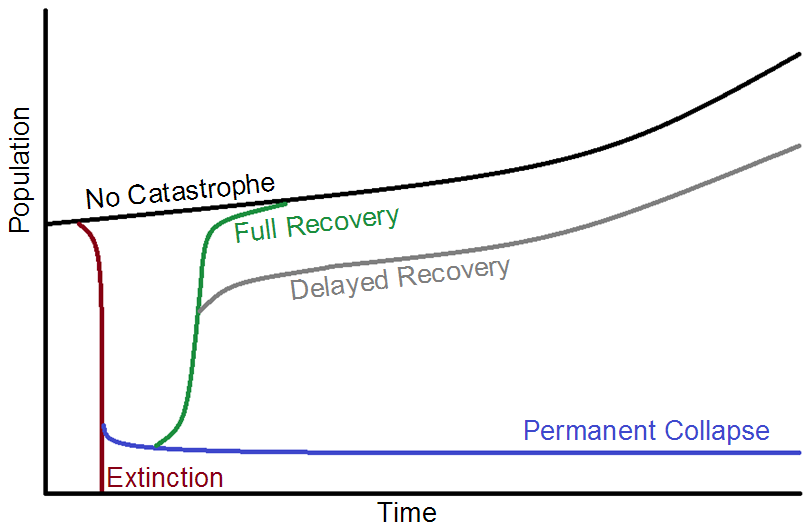

From certain perspectives, it is especially important to consider the long-term fate of survivor populations. This includes not just the people alive at the time of the initial catastrophe, but also their children, their children’s children, and subsequent generations into the distant future. A global catastrophe could cause a steep decline of the human population. If the initial catastrophe causes human extinction, then the decline goes all the way to zero and it would presumably stay at zero in perpetuity. However, if the survivors have at least a “minimum viable population”, then they may be able to demographically recover. A long-term evaluation of global catastrophic risks involves assessing the trajectories that survivor populations would take.

Despite the importance of the aftermath of global catastrophe, the topic is often neglected. Instead, much of the attention goes to assessing and reducing the probability of global catastrophe. To an extent, this is entirely reasonable: it is of course better to prevent global catastrophe from occurring in the first place than to try to mitigate the aftermath. It is also understandable that some may shy away from working on the aftermath due to the grim nature of the topic. Nonetheless, the topic merits attention, even if that means thinking the unthinkable. The stakes are too high to ignore.

The aftermath of global catastrophe is arguably one of the largest and most important points of uncertainty in the study of global catastrophic risk. The uncertainty is large because the aftermath is a complex and unprecedented phenomenon. There has never been a civilization-ending global catastrophe, which is of course a good thing, but it does mean we lack data on the aftermath. Furthermore, there has been little research attempting to study the aftermath and reduce the uncertainty. The uncertainty is likewise important because how well humans would fare in the aftermath determines the long-term severity of global catastrophes, as sketched in the graph above.

To reduce the uncertainty and support efforts to improve conditions for survivors, GCRI is a longstanding contributor to work on the aftermath of global catastrophe.

Featured GCRI Publications on the Aftermath of Global Catastrophe

Pandemic refuges: Lessons from two years of COVID-19

Refuges could protect some people from global catastrophes, but only if people are willing to do what it takes to stay safe. During the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, some places served as refuges by avoiding widespread transmission of the virus and going for extended periods with near-zero case numbers. This paper uses case studies of Australia and China to study what it takes to maintain a successful refuge from pandemics and other global catastrophes.

Long-term trajectories of human civilization

What will be the fate of human civilization millions, billions, or trillions of years into the future? It is uncommon to ponder such long time scales, yet from a variety of perspectives, they are of very high moral importance. This paper studies several possible long-term trajectories, including the radically good and catastrophically bad. It analyzes of the long-term prospects of the survivors of global catastrophe, including the probabilities of survivors losing and later rebuilding civilization.

Uncertain human consequences in asteroid risk analysis and the global catastrophe threshold

Asteroids are an important case study because they are arguably the most well-understood global catastrophic risk. However, this paper shows that asteroid risk analyses are more tenuous than they sometimes claim, due to high uncertainty about how humans would fare in the aftermath of asteroid collisions, especially for the more catastrophic collision events. This shows why the aftermath of global catastrophe is a large and important point of uncertainty in the study of global catastrophic risk.

Full List of GCRI Publications on the Aftermath of Global Catastrophe

Baum, Seth D., 2023. Assessing natural global catastrophic risks. Natural Hazards, vol. 115, no. 3 (February), pages 2699-2719, DOI 10.1007/s11069-022-05660-w.

Baum, Seth D. and Vanessa M. Adams, 2022. Pandemic refuges: Lessons from two years of COVID-19. Risk Analysis, vol. 43, no. 5 (May), pages 875-883, DOI 10.1111/risa.13953.

Brown, Jared, 2020. The Defense Production Act and the failure to prepare for catastrophic incidents. War on the Rocks, 14 April.

Baum, Seth D., 2019. Why catastrophes can change the course of humanity. BBC Future, 8 April.

Baum, Seth D., 2018. Resilience to global catastrophe. In Benjamin D. Trump, Marie-Valentine Florin, and Igor Linkov (editors), IRGC Resource Guide on Resilience (Vol. 2): Domains of Resilience for Complex Interconnected Systems. Lausanne: EPFL International Risk Governance Center. Available at https://irgc.epfl.ch/risk-governance/projects-resilience.

Baum, Seth D., 2018. Uncertain human consequences in asteroid risk analysis and the global catastrophe threshold. Natural Hazards, vol. 94, no. 2 (November), pages 759-775, DOI 10.1007/s11069-018-3419-4.

Baum, Seth D., Stuart Armstrong, Timoteus Ekenstedt, Olle Häggström, Robin Hanson, Karin Kuhlemann, Matthijs M. Maas, James D. Miller, Markus Salmela, Anders Sandberg, Kaj Sotala, Phil Torres, Alexey Turchin, and Roman V. Yampolskiy, 2019. Long-term trajectories of human civilization. Foresight, vol. 21, no. 1, pages 53-83, DOI 10.1108/FS-04-2018-0037.

Baum, Seth D., David C. Denkenberger, and Joshua M. Pearce, 2016. Alternative foods as a solution to global food supply catastrophes. Solutions, vol. 7, no. 4, pages 31-35.

Baum, Seth D., David C. Denkenberger, and Jacob Haqq-Misra, 2015. Isolated refuges for surviving global catastrophes. Futures, vol. 72 (September), pages 45-56, DOI 10.1016/j.futures.2015.03.009.

Baum, Seth D., David C. Denkenberger, Joshua M. Pearce, Alan Robock, and Richelle Winkler, 2015. Resilience to global food supply catastrophes. Environment Systems and Decisions, vol. 35, no. 2 (June), pages 301-313, DOI 10.1007/s10669-015-9549-2.

Baum, Seth D., 2014. Film review: Snowpiercer. Journal of Sustainability Education, vol. 7, December issue (online).

de Neufville, Robert, 2013. The sixth extinction – Book review: Scatter, Adapt, and Remember. Anthropocene blog, 27 May.

Maher, Timothy M. Jr. and Seth D. Baum, 2013. Adaptation to and recovery from global catastrophe. Sustainability, vol. 5, no. 4 (April), pages 1461-1479, DOI 10.3390/su5041461.

Baum, Seth, 2012. Hurricane Sandy hints at the perils of global catastrophe. Scientific American Blogs, 6 November.

Baum, Seth, 2012. Global disaster recovery. FutureChallenges, 17 April.

Image credits: rubble: Voice of America; grain silos: Leaflet; population graph: Seth Baum