About Global Catastrophic Risk

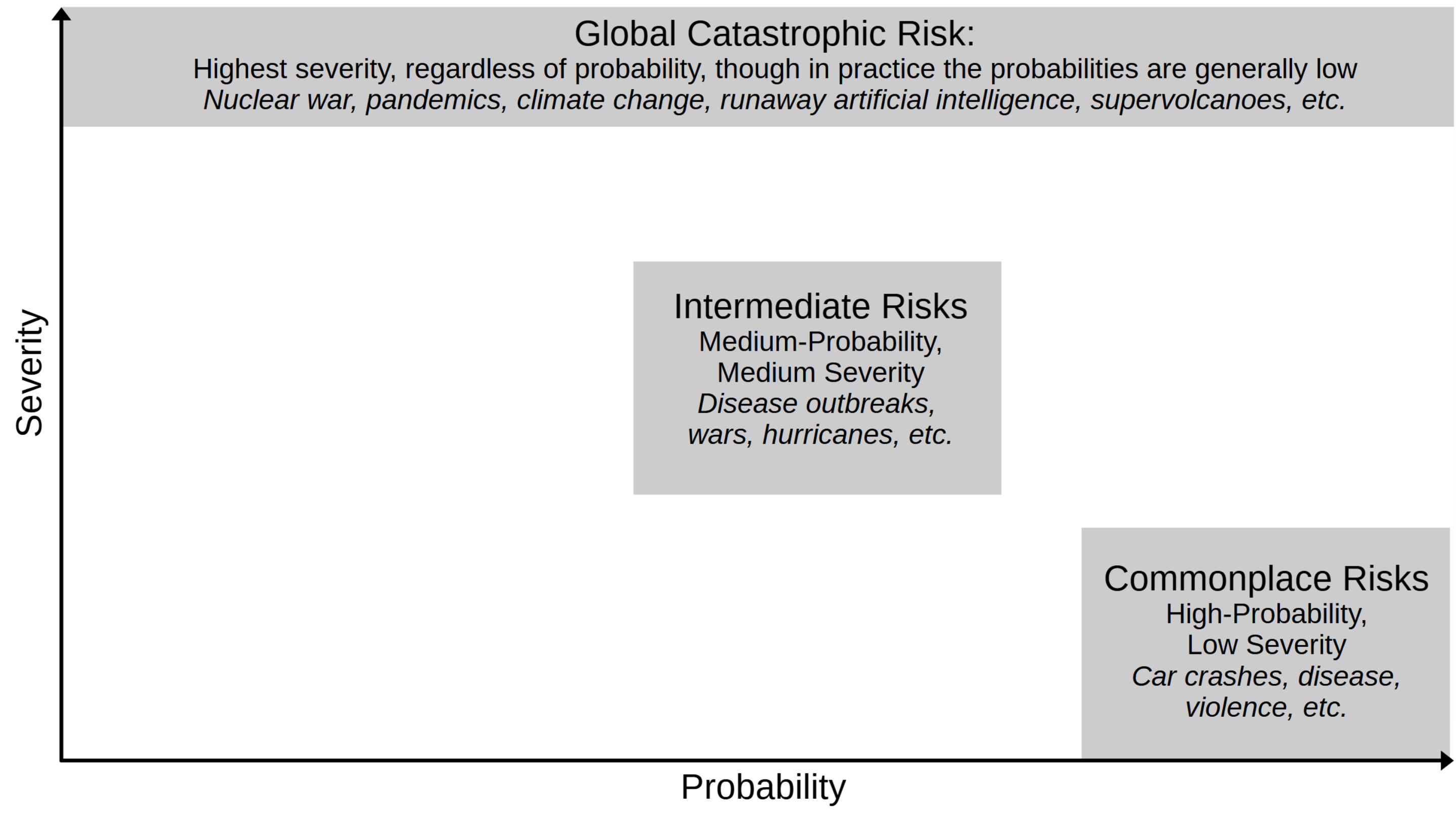

Catastrophes happen every day. A disease that sends someone to the hospital. A car crash that kills someone’s children. An act of violence from a war that still hasn’t ended. These events are all tragic in their own right and deserve to get plenty of attention. Meanwhile, lurking in the background is the risk of larger catastrophes, events that do not happen every day, but if and when they do happen, the scale of the harm is much larger. A disease that spreads into a pandemic. An accumulation of pollution that disrupts the global environment. A local war that expands and escalates into something much worse. These lower probability and higher severity risks may not be day-to-day concerns in the same way as the every day risks, but given their larger severity, they too can merit attention.

Global catastrophic risk is at the extreme end of low-probability, high-severity risk. More precisely, global catastrophic risk is the extreme end of high severity, regardless of probability, though in practice the probabilities are generally low, especially compared to more commonplace risks such as disease, car crashes, and war. Global catastrophe can be defined in many ways, but the general idea is of events that could significantly harm or even destroy human civilization at the global scale. These are the worst-case scenarios, the events that may end life as we know it, the harms so devastating that humanity may never recover. Included here are scenarios that result in the collapse of human civilization, the extinction of the human species, and outcomes that are so horrifically bad that they are actually worse than extinction. Of course, events of this sort do not happen every day. It is possible that they will never occur. However, it is also possible—however likely or unlikely—that they will sometime occur. If and when they do, it would mark a dark turn for the human species and perhaps also for the rest of the world. The stakes are incredibly high, making it worthwhile to explore what can be done to reduce the risk.

Conversations about global catastrophic risk often identify specific risks. Severe global pandemics—even more severe than COVID-19. Nuclear war, especially a large nuclear war that may cause nuclear winter. Climate change, especially more extreme climate change scenarios. Artificial intelligence, in particular the possibility of artificial intelligence taking over the world and killing everyone. Various extreme natural disasters, such as a supervolcano eruption, a large asteroid or comet colliding into Earth, or the explosion of a star in a nearby part of the galaxy. GCRI has worked on many of these risks, especially artificial intelligence and nuclear war. Additionally, GCRI has advanced a cross-risk approach to studying and addressing global catastrophic risk that recognizes important interconnections between the risks. It can be advantageous to think less in terms of specific, isolated global catastrophic risks and more in terms of the entirety of global catastrophic risk as an interconnected whole.

One especially important cross-risk topic is the aftermath of global catastrophes. Most global catastrophe scenarios do not result in immediate human extinction: there are survivors who must cope with a radically altered world. Much depends on how the survivors fare. If they succeed, the human population and civilization could recover and flourish. If they fail, the population could persist in diminished form or eventually die out. Likewise, there are measures that can be taken now, before the catastrophe occurs, to aid the survivors and facilitate their success. In particular, society today can prepare resources, information, and infrastructure that the survivors could use. However, such preparedness measures require society today to engage with some very grim and uncommon scenarios. It is perhaps unsurprising that little such work has been done. Therefore, GCRI has worked on the aftermath of global catastrophe by articulating its importance, analyzing aftermath scenarios, and developing ideas for how to support survivors.

The study of global catastrophic risk is not easy. It requires deviating from the common empirical approach to risk analysis, in which data on past adverse events is used to estimate the probability and severity of potential future events. This approach is only suitable for more commonplace risks. For example, the risk of a person dying in a car crash can be estimated by compiling and analyzing data on past car crashes. While that person has presumably never previously died in a car crash, many other people have. There is robust data on car crashes, which can be segmented by attributes such as location and demographics to obtain a reliable estimate of the risk of any given person dying in a car crash. The same data-driven approach can be used to estimate the risk of other more high-frequency events. This is the primary basis for setting insurance premiums and is also used for many other forms of risk governance.

Analysis of global catastrophic risk cannot rely on past event data. In a sense, there is no such data: modern global human civilization has never previously been destroyed. Importantly, this does not imply that the probability of global catastrophe is zero. Just because something hasn’t previously happened, that doesn’t mean that it couldn’t: past performance does not guarantee future results. Therefore, instead of using past event data, the study of global catastrophic risk must pull together whatever relevant information can be obtained. Past events that bear some resemblance to possible future global catastrophe scenarios. Mechanisms for how global catastrophe could occur. Expert judgment on specific aspects of global catastrophic risk—though use of expert judgment should proceed cautiously, given its potential to be misused. It is not possible to assess global catastrophic risk as precisely as the more commonplace risks, but some rigorous assessment is nonetheless possible. Humanity does not need to fly blind. GCRI’s work on risk and decision analysis develops and applies methods for studying global catastrophic risk.

Despite the importance of global catastrophic risk and the potential to make progress on it, it remains the case that humanity is mostly focused on other matters. Contemporary human society is highly pluralistic in terms of its values, interests, and concerns, and more commonplace matters often get higher priority. Given this reality, efforts to address global catastrophic risk can take two basic forms: a direct approach, in which people are persuaded to care more about global catastrophic risk and act accordingly, and an indirect approach, in which people are persuaded to take actions that advance whatever they already care about while also helping on global catastrophic risk. Both approaches have an important role to play, and the best option is often a mix of both. However, GCRI’s work on solutions and strategy has emphasized the indirect approach due to the tendency for people to not prioritize global catastrophic risk and the accompanying need to build coalitions with people who are focused more on other issues.

Image credits: risk diagram: Seth Baum; middle image: Hazmat: U.S. Air Force; crops: Marc Ryckaert; naval fleet: U.S. Navy; turbogenerator: Siemens; bottom image: ice age Earth: Ittiz; electron microscope image of virus: NIAID; asteroid collision: NASA; space weather/magnetosphere: NASA; gamma ray burst: NASA; volcano eruption: Raden Saleh